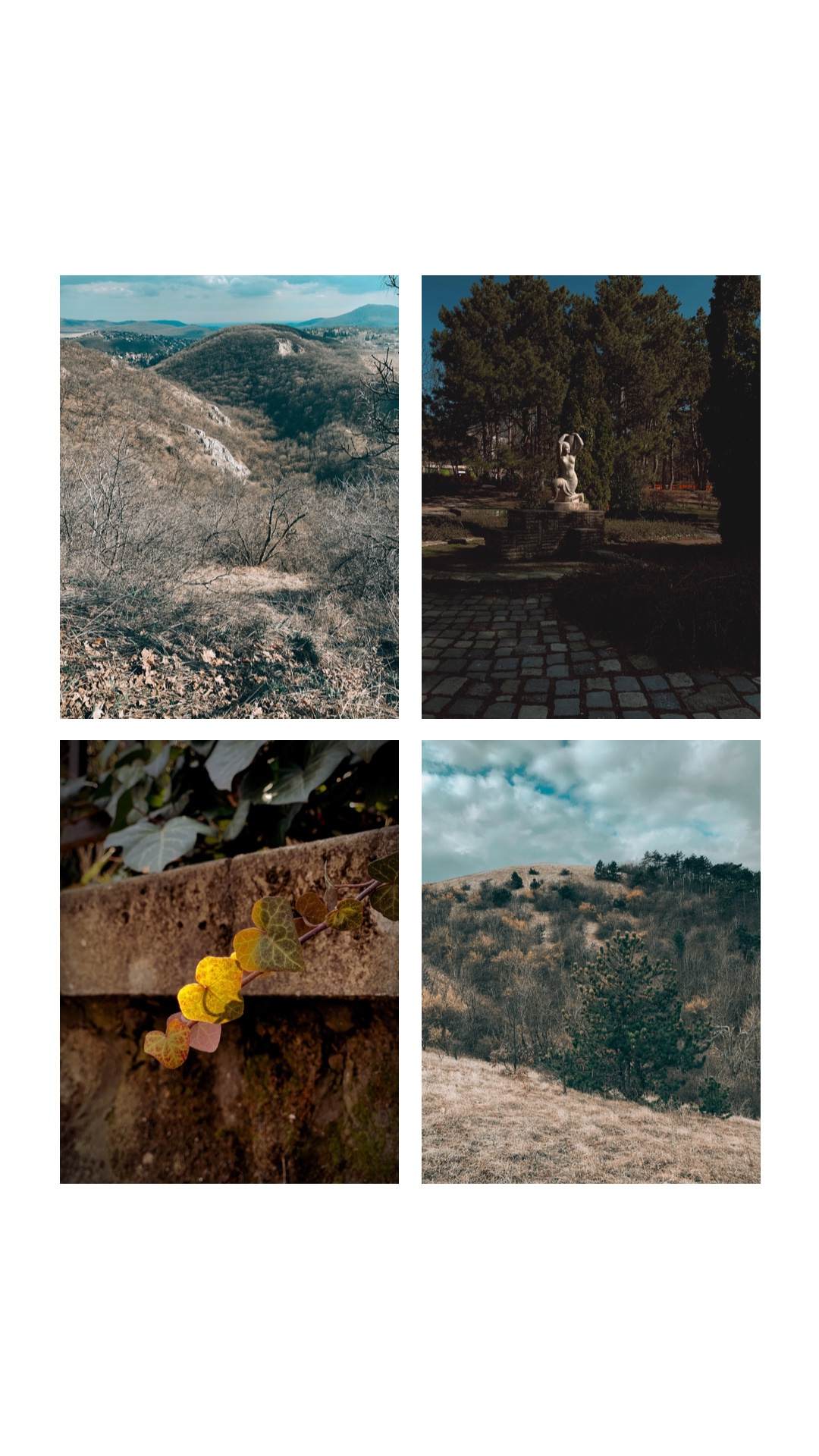

another weekend, another (exceedingly long) edition of enda lettere, a newsletter about landscapes and literature. let me begin by expressing my heartfelt gratitude to you all: in these past weeks i’ve been inundated with your words of encouragement and praise and kindnesses—thank you with all my heart. your feedback means the world to me, a world full of ideas, possibilites, and splendor. cue ‘splendor’: today’s walk takes us through the parks and fields and forests and gardens of a morbidly idyllic Budapest in the spring of 2020.

“And I saw the ancient days. There were bells tolling and wreaths tossed and women turning in circles and there were bees performing their life-cycle dance and there were great winds and swollen moons and pyramids crumbling and coyotes crying and the waves mounting and it all smelled like the end and the beginning of freedom.”

Patti Smith: Year of the Monkey

we are all falling into a familiar routine—it has been only a couple of days since i am in Budapest, at my parents’ house in the Buda Hills, somehow, inexplicably free, yet it still feels like a short vacation, a few days of the usual: social obligations, short walks, a bit of work, scurrying here and there, play pretending to be busy, putting off the important things indefinitely. a sunday is a sunday, the news on television are just news, mere noise added to the noise of the cooker hood in the kitchen.

the sparrows have a busy day, too. their chirping grows louder and more agitated as the shadows recede in the garden under the pale greengold rays of early spring sunshine. a cool breeze ruffles wispy clouds in the sky, still a shade of deep winter blue, with a hint of a subtle golden hue, the promise of warmer days. it’s impossible to stay put. it’s impossible to stay inside. so i nip out and head to the nearby forest where a weave of trails inevitably leads to wondrous places. but such is the liminal space, a wide green-yellow sash of hills and woods between the capital and the surrounding villages.

the view from Kis-Hárs-hegy in June 2020

to walk here again feels disorientating; it makes me slightly uncomfortable. who is this me walking alone in my childhood playground, untethered? is it a person who had fled responsibility in the big city? is it a wayward child? is it someone new i haven’t met yet? even at my most vulnerable, the forest embraces me, i quickly become invisible, a woodland creature of nimble steps.

i amble along a well-known route to the Zsíros-hegy, and where the many paths converge, there had been a hut, the remnants of its outer walls still visible on the clearing. that is where i first see them, the Conservative Gentleman and the Precocious Little Boy, sitting on the low stone wall in the sun. they’re wearing nearly identical clothes. with their pleated trousers and long socks and woollen jumpers these two could be time travellers from 1932 and maybe they are.

there is a sense of happy nonchalance around them as they sit there, legs crossed, eating boiled eggs and drinking coffee. the sleeves of their olive green jackets brush lightly. i watch them from a distance, the breeze carrying their voices towards me. the Boy tells about having seen one lonely, exquisitely cream-colored lamb standing coyly in the shade on a summer afternoon, its sad eyes filled with longin. the Boy approached it quietly and kept petting its pristine fleece, little fingers burrowing in its supple thickness, the lanolin-scented calm, the deep yearning to keep that ewe, to walk home with it, to walk everywhere from that day on with the gentle, lonesome lamb in tow. the Boy peers at the man, hesitating. the Gentleman smiles a broad, gentlemanly smile. “what would you do if that lamb appeared here right now, i wonder. i bet you would call that synchronicity,” he says, his voice sunny, full of mischief. “i’d call it a pastoral idyll, i guess” the Boy shrugs. they both laugh and go on arguing the notions of apophenia and synchronicity.

how odd. did my imagination conjure these characters in an attempt to lampshade my awkward nostalgia? for it feels like nostalgia, this misaligned yearning for the 1930s, a fascinating world of light and shadow, modernism and traditionalist sentiments, a rapidly changing society full of new ideas, full of dangerous tension, and unhealed trauma.

strangely enough, in that politically charged decade hiking became a great equalizing force in the middle class: after the Trianon treaty had rendered the mountainous areas on formerly Hungarian soil largely inaccessible, slowly, very slowly, urban youth began to explore the hills of Buda and the surrounding german- and slovakian-speaking villages on foot. whereas Jews were expelled from tourist associations in Austria amidst the growing anti-semitism of the 1920s, in Hungary hiking amalgamated groups of different religious and ethnic backgrounds. in other sports and pastime activities the jewish, christian and workers’ clubs and associations remained divided, whereas on hikes and picnics it was not uncommon for young people to meet and befriend members of the out-group. thus, a decade after the spanish flu and the great war, in the long shadow of the great depression and the rapid rise of Hungary’s own brand of nazism, the Arcadian notion of walks in the Buda Hills offered the most perfect illusion—the illusion of maintaining healthy, modern habits, cultivating companionship, and partaking in the simple pleasures despite an increasingly hostile milieu.

in the spring of 2020 i recognize a similar magnetic pull in myself, as life as we have known it grinds to a halt in the wake of the pandemic. a sunday is not quite a sunday anymore, the news not just the news, although the noise to signal ratio is still abysmal. suddenly, anxiety riles up everyone around me, and during the first few weeks the uncertainty is numbing: i was going somewhere, i recall with a shudder, but with the borders closed now, the green-yellow sash of hills and wood is all that remains. and it is impossible to stay put, impossible to stay inside, so more often than not, i walk. and when i get tired, i lie down. and when i get bored of the trails, i abandon them or re-discover old favorites and find new paths to follow.

it was impossible to photograph with the eye only—a single iris somewhere above Remete-szurdok in April 2020

the next time i see them, i am way more surprised than they are: i have never ever seen anyone on the perch above the ravine. the narrow valley below is one of the most popular short hikes in the vicinity with major trails running along the creek on the valley floor, and across the steep, rocky side to a handful of caves, but the overhang above the caves has been forgotten, even by locals.

the pale grasses had grown tall between the battered islands of the rocks. purple and yellow irises poke their crumpled heads out from under the blades of grass, struggling to break free and unfold their blossoms, softer than a little girl’s shoulder. every cautious step on this long-forgotten, narrow path feels unusually quiet, as if i was walking on a silken carpet. gnarly, stunted oak trees demarcate the expanse of woods towards the rounded and flat top of the hill. the air is heavy with the warm scent of wild thyme, the cool minerality of the rocky ground, and the sweetness of dried grass. ravens gather somewhere, their cawing quite macabre over the tops of the trees. the wind carries the whine of a chainsaw from the hamlet at the far end of the ravine.

there is a bend around a particularly large rock jutting upwards, shielding a grassy patch big enough for two and there they are: the Conservative Gentleman and the Precocious Little Boy in beautiful repose, sunning themselves. again, they look comically identical despite the evident difference in size and age. their marinière shirts are in stark contrast with the more chaotic patterns of our surroundings. what are they to each other, i wonder. then i go on to greet them with a nod, and they gaze right through me for a moment before sinking their heads back onto the grass. not to seem idle, the Boy sits up a moment later and begins to fidget with a camera. the lens points at the delicate blossoms of an iris. the Gentleman observes every movement from behind his round sunglasses with lazy interest. “you are not going to take a picture of that, are you?” he asks. they look at each other, silence hanging between them.

maybe the Boy wouldn’t, but i am, day after day, on every walk. i take photos of snowdrops, crocus, violets, plum and early cherry blossoms, tulips, narcissi, almond and apple trees. as if a mysterious life force erupted from beneath the ground, prying the world open with strong, steady hands, spring crashes into the gardens, parks, and forests. this cannot be real, i mutter to myself day after day, on every walk. i am in utter, suspicious disbelief, and laugh at my unease awkwardly: if i take a photo of these flowers, is it proof of their existence, proof of mine? do they become real and fixed, for i seem to be incapable of grasping that we all seem to be trapped in perfect, eternal spring. or is the whole thing just sentimental trash, an iris an iris an iris?

“we are in Arcadia!” i exclaim one morning, woken by the goldenflute call of a single, perfect oriole.

Arcadia is an early version of an utopia, its name stemming from a secluded, mountainous region of Hellenic Greece, the rumored home of the nature deity Pan and his followers, nymphs and dryads, a merry bunch.

if we want to find the original landscape architect, we’ll need to turn to Vergil again, as this powerful vision is his invention, following the blueprint of traditional pastoral idylls laid out by Theocritus. but then again, Vergil’s originality that gave us many an updated view of landscapes, characters, and dramaturgical solutions of Hellenic classics cannot be kept at bay. in his Eclogues he reforms and perfects the notion of pastoralism and its typical setting: mythical, unspoiled Arcadia, now an easy identifier for a landscape untouched, where man, beasts, and deities live in eternal harmony, where love is the greatest power that be (love conquers all, mind you!). imbued with the life force of love, all creatures live out their days in perfect unity. bees, sheep, goats, and birds thrive, flowers bloom, and poets sing of lovers pining for each other in sweet surrender. the notion of Arcadia takes an imagined, healthful balance of nature as its basis: there are still hunters and the hunted, seasons come and go—Vergil understands and celebrates the transient and circular ways of nature.

however, this ideal state is strictly mythical and hence, unattainable. compared to other utopian visions and myths of the golden age, Arcadia is expressly a desired landscape, because it is based on that existing mountainous region of Ancient Greece. Arcadia cannot exist, as mankind had lost touch with nature the moment man began to rely on agriculture—the moment man began to view land either as hostile or arable was the also the moment man began to create geography.

for weeks i have been riding the waves of hope and desperation. time and again i wish everything could just go back to the way it was. i ponder whether the denizens of this city will begin to bond with their immediate environment, rediscovering the peeling layers of Budapest, the frontiers where its architecture tears into nature.

i descend the old german calvary hill on the steep way of the cross, and think of the ancient Danube Swabian aunties routinely making the pilgrimage every year on Easter. a flat and wide drove way leads across the fields, towards Pesthidegkút, once a german-speaking town, now part of Budapest’s 2nd district. i spot the Conservative Gentleman and the Precocious Little Boy walking hand in hand towards the abandoned greenhouses. they stop and marvel at the crescent of hills, a frame of deep seafoam green and burnt siena and ocher, the fields between them and the greenhouses a deepening golden yellow. there is a purple dusk over the landscape, a handful of bright stars piercing the festive shawl of the sky. the twilight strangely gives everything sharper contours, as if the landscape was turning into a painting of very precise brush strokes. every angle, every slant lives and emanates the energy of the day, the world shedding the power of the sun, exulting. it is only the three of us watching this scene now. the Gentleman turns around, his movements fluid and graceful, spreading his arms in an attempt to embrace the wholeness of the world.

“look at all the hills, it’s an amphitheatre!” he exclaims. “better yet, imagine we are now standing in the middle of a volcanic caldera. it’s wonderful!”

abandoning all sorts of trails near Hármashatár-hegy in May 2020

if we read the eclogues and allow our imagination to open up a gate through which we step inside the arcadian scenes, we’ll find that all these images are filled to the brim with textures, various bits of activity and movement, either in the literal sense, or through the memories of characters (for the Arcadian idyll is only complete with its human characters: heroes, hunters, shepherds, poets), but never on a scale of the epic plot. as a mythical place, Arcadia is an amphiteatre indeed, that of an improbable human experience and the act of remembering youth.

however, many a misunderstanding comes from how we view the powerful, mythical image of arcadia today. the art-educated elite, mainstream post-modernism, popular and youth cultures identify the notion of humans’ connection with untouched nature as mere kitsch. indeed, Arcadian pastoralism is simple, straightforward, beautiful—the wistfulness, the nostalgia felt about the loss of such an uncomplicated and uncorrupted lifestyle is effortlessly identifiable for anyone. even if one truly and unquestionably experienced the rapturous intensity of becoming part of nature, it would be best left untold. otherwise we’d run the risk of being sentimental, ridiculous even.

the truth is, the day and age we live in alienates us from our own experiences. we talk of ‘glorious boredom’ when confronted with the gradual emptying out of the conscious mind on long walks. we ought to feel guilty when we are overwhelmed by our longing to connect on a metaphysical level, or whenever we see our inner turmoil reflected in the mirror of nature; our souls lag behind and experiences of rapturous intensity are snuffed out by cartesian materialism.

but does that render our very experience in nature invalid? does that render any description of transcendence invalid?

and if not, do we have the necessary vocabulary to convey meaning?

even in the gutter, they bloom—violets near my parents’ house in March 2020

“Metamorphosis, crystallization, rebirth, horizon, discovery, phoenix, lustrum, resolution, decision, revolution; I would need to use all these words with mastery to describe what I felt.”

Paulo Emílio Sales Gomes: Her Times Two: “First Carnet”

big words, big words, i think, as i trod along the winding path towards the summit. i call it a ‘summit’, but it’s just the top of a steep hill with a tower, marled rocks, and ancient trees. it is a dizzyingly hot day, the heat humming a monotonous melody. a carpet of silvery russet and emerald green beckons, and i sink down and spread my limbs happily.

i close my eyes and still see everything. first the horizon falls away, the forest begins to lose context. i try to hold my breath. the sun is white above me, a jewel come alive, a deity of foreign, unbearable magnificence; it reaches out to my face and my hair and covers my eyes with its radiant little hands, and the grass carresses the skin behind my ears and the nape of my head, the rustling leaves beneath me smell of sweet decay. the sun’s fingertips touch the linen weave of my jacket and my arms and neck and collarbones and my cheeks. the whole world turns into a mere colorspace, devoid of form or meaning. for a white-hot moment the borders of how i perceive the world and myself in it dissolve and there is no body, no soul, no trees, no sun, no blades of grass, no twigs, no birds, no bugs, no path, no clearing, no words or thoughts. within everything there’s the void. in Arcadia i cease to exist for a moment.

the Arcadian myth is not one of immortality. amid the idyllic setting, Vergil shows us the tomb of the hero, or rather rock-star Daphnis. “I was Daphnis in the woods, known from here to the stars, / lovely the flock I guarded, lovelier was I,” the humble inscription reads. this is the very moment of the myth where we are reminded of death, a moment calling for a succint summary: “et in arcadia ego” or “even in Arcadia, i am.” a bony hand jutting upwards in a meadow full of flowers so matter of factly, that it defies the post-modern notion of kitsch. this memorabe aspect was popularized in the Italian Renaissance—a new European golden age blooming in the aftermath of Black Death. maybe it is just a remnant of the medieval fascination with the morbid thanks to the unprecedented devastation caused by the plague. maybe it is a fundamental truth we can only stomach if it exists within the perfectly beautiful.

the backdrop to this riotous spring is an unrelenting stream of news and images of people dying. first it’s the old, rich, white people in the west. then the chronically ill. then the deprived and the oppressed. the black swan spreads its wings and the world as we have known it undergoes changes of unfathomable depth. the world as i have known it splits into half. and i realize with terror, that the pieces don’t fit anymore, i can’t mend my world, i can’t make neither my personal experience of rapturous intensity, nor the everyday horror of the pandemic unseen, and i feel a particularly heavy sense of guilt.

even so, there is a strange equilibrium in exceptional beauty and exceptional misery co-existing in the extreme in the spring of 2020, transcending myth and cruel history. “et in arcadia ego” is not just a plot device of antiquity, or a trite trope of old paintings anymore—it is un-mythical, naked reality.

and with that i lay to rest my ambitions to replace the London Review of Books in your lives. next time, i promise to bring you a rather light-hearted collection of tidbits from the Mosel.

until then wishing you light steps,

n.